This is an excerpt from Eric Hoffer's 1951 book The True Believer:

"Those who would transform the nation or the world cannot do so by breeding and captaining discontent or by demonstrating the reasonableness and desirability of the intended changes or by coercing people into a new way of life. They must know how to kindle and fan an extravagant hope. It matters not whether it be hope of a heavenly kingdom, of heaven on earth, of plunder and untold riches, of fabulous achievement or world dominion. If the Communists win Europe and a large part of the world, it will not be because they know how to stir up discontent or how to infect people with hatred, but because they know how to preach hope."

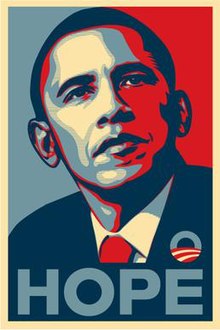

Barrack Obama, as we all know, ran for president in 2008 on the platforms of "change" and "hope," (his primary book was titled The Audacity of Hope, the secondary being Dreams of my Father). The Democratic party's underlying principle is progress; so blatant is this that democrats often self-identify as "progressive liberals." More recently, the 99% movement has articulated a more distinct demand for change, and the crusade for diversity and multiculturalism in universities, with the blue party's blessing, has achieved something of a religious orthodoxy in tenor. In short, the Democratic party in its current form is the quintessential foundation of a rising mass movement.

It should be noted that I first came across Hoffer in Max Bloomenthal's excellent exposé, Republican Gommorah, so I hope it's clear from the start that I don't think the Democratic Party is the only party susceptible to the dangers of mass-movements. The Christian right within the Republican party, the Tea Party within the "libertarian community" (forgive the oxymoron there), and various sub-groups within larger religious, social and political identities have all, at various times, succumbed to the luring power of fanatical mass-movements. The modern Democratic party is one of these that seems to be largely overlooked.

There are two assumptions that the radical left's political ideology relies on: one, that we know enough about what we're doing in social and economic policy to accurately predict what will happen when we change it, and two, that the situation we live in is in dire need of changing. These two assumptions are both quite separately debatable. Is the change we seek both desirable and possible? Is life in the status quo really so bad? The subject of more recent psychological research has been happiness, much of which vindicates De Tocqueville's observation of the French, who "found their position the more intolerable the better it became."

Unintended consequences have turned many a well-intentioned social programs into disasters. Indeed, as Daniel Dennett said, "if there is one thing we learned from the 20th century, it is that good intentions aren't enough." The road to Hell really is paved with good intentions, and the incredible power of "hope," "dreams" and "progress" to enact social change allows for the construction of such a road with alarming alacrity. (Just remember that "you didn't build that," and it will all be okay).

Most of Hoffer's examples are 20th century examples like the Nazis, fascists, and various other religious and nationalist movements. This is not to say that the principles do not apply today though. History's rhyming tune has to return to the chorus every so often, and the Democratic party, with its grand rhetoric and Utopian vision, provides a very plausible candidate for just that kind of political reincarnation. In essence, the donkey speaks more wisely as the voice of Orwell in Animal Farm than as the mascot of its corresponding political movement. We may disagree with old Benjamin about the cynical nature of the eternal state of affairs resulting from the human condition, but the grand calls for change are not new to this century, this generation or this president. It has all happened before.

I will finish with another excerpt from the same chapter of Hoffer:

"When hopes and dreams are loose in the streets, it is well for the timid to lock their doors, shutter windows and lie low until the wrath has passed. For there is often a monstrous incongruity between the hopes, however noble and tender, and the action which follows them. It is as if ivied maidens and garlanded youths were to herald the four horsemen of the apocalypse."

No comments:

Post a Comment